Re: Huurlingen

Eén vraagje hierbij : zie jij de structuur dan militair? Hierbij bedoel ik: zou er een aangewezen leider zijn?

Eerlijk? Ik weet het niet, maar er hoeft volgens mij geen aangewezen leider te zijn.

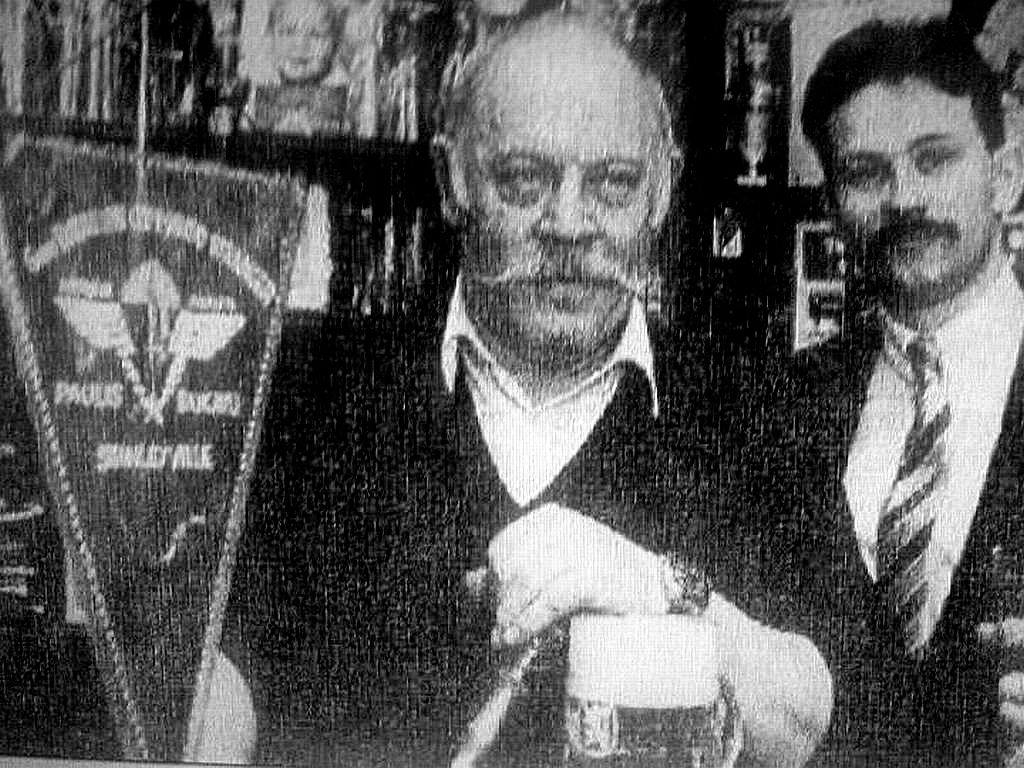

Charles Mazy in café "La Renaissance”:

Deze foto komt waarschijnlijk uit onderstaand artikel uit 1987. Het is een reportage over café "La Renaissance". Links op de foto staat Charles Masy, rechts staat James "Jim" Shortt, de auteur van dit artikel.

Brussels’ Bar Simba - Saloon for Mercs

“La Renaissance” reads the sign above the door at the old Brussels building. But here in Belgium, and indeed, around the world, 42 Rue Marche au Charbon is known to military veterans by another name - Bar Simba. Before the Katanga Brewery closed, it was the only watering hole outside Africa where former Congo mercenaries could drink Simba-Tembo beer and recollect their part in the short-lived Republic of Katanga.

Bar Simba is also the headquarters of the Brussels branch of the French Foreign Legion amicale (association), and The Force Publique. The Force Publique, officered by Europeans, maintained order in Belgium’s equatorial African colonies.

Located near the central police station. Bar Simba boasts a clientele drawn from active-duty military, police and veterans. Veterans from World War I to the Falklands have drunk, sung and, on not a few occasions, passed out here. The time-honored custom of donating your cap badge, unit insignia, airborne wings or commando qualification patch is evidenced by the massive display of elite unit insignia that hangs behind the bar. Green Berets, SEALs, Rangers and Marines have “swapped lies” here with their European counterparts, as is witnessed by the bits of America they’ve left behind at this international “rogues’ gallery.”

I first encountered Bar Simba while leading a three-man combat training team at the Para-Commando school of the Belgian army. The Belgian military Etat Major (army headquarters) had asked me to bring a team to establish a close-quarter battle syllabus for the Belgian Para-Commando Regiment. Over a beer in the regiment’s Sous-Officiers (NCO) club it was suggested that I visit Bar Simba. Two hours later, I arrived and was greeted by a legion veteran singing in French:

Les Druses s’avancent a la bataille

En avant, legionnaires a rennemi

Le plus brave au combat comme toujours

C’est le Premier Etranger de Cavalerie

This song of the 1st REC ( Regiment Etranger de Cavalerie, Regiment of Foreign Cavalry) - the elite of the legion before the paras - recalls the Foreign Legion battles against the Druze in Syria. Times haven’t changed much.

My blurred memory of that evening alternates between endless rounds of strong, black Belgian beer, Chimay Trappiste; stories of wars the media missed (thankfully); and the songs - Anne-Marietje , Fallscbirmjagerlied and Op Walcheren, the music to which the Para-Commandos march. The legion veterans replied with Le Boudin, Legionnaire del'Afrique and Contre les Viets - the last being sung by a 1st BEP (Bataillon Etranger de Parachutistes, Battalion of Foreign Paras) veteran of Dien Bien Phu.

Le Patron - their host - at Bar Simba is Charles Masy, a veteran of wars in Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Charles Masy’s father was a Corps of Engineers veteran of the trench fighting in World War I. By his 14th birthday, Charles’ Belgium was again occupied by the Germans. At the age of 17, he joined the resistance movement. His closest scrape with the enemy came when he was arrested by the Gestapo. Charles convinced his interrogators that they had seized an innocent youth, and he was released. He continued to fight with the resistance until 1945, when he applied to join the Belgian SAS (Special Air Service).

When the war ended, the Belgian SAS battalion was handed back to the Belgian army. It was redesignated 1 Parachute Battalion-SAS. “I joined 1 Para, which still wore the SAS winged dagger as its badge at Tervuren in 1945,” said Charles. “I completed my Para-Commando training, kept my nose clean and rose through the ranks. I chose to become a professional soldier.”

Like most European countries that had colonial possessions, the post-1945 period was a busy time for the Belgians. The elite Regiment Para-Commando saw its share of the action. Belgian possessions in Africa - based around the equator and including the area covered by the current African states of Congo, Zaire, Rwanda and Burundi - had been kept relatively peaceful since 1886 by the Force Publique. By the 1950s the force was 30,000 strong, highly disciplined and smartly turned out. But by 1953 the winds of change were blowing. The Para-Commando was tasked with assisting the Force. The regiment helped to preserve order, often by parachuting into villages in rebellion or under siege.

On 30 June 1960, the Belgian possessions were given their independence, starting with the Congo. Force Publique was rechristened Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC). In July 1960, units of the ANC mutinied, massacring white settlers and Belgian officers. The Para-Commandos moved in. The rebellion was aggressively put down. All but 300 of the original 2,800 members of the ANC were discharged and the remainder were placed under the command of a former NCO who had been promoted to colonel.

On 11 July, with the backing of the Belgians, the mineral-rich province of Katanga declared itself a separate country under Moise Tshombe. The United Nations opposed the new republic and sent in troops to dismantle the country and restore it to the Congo. If the United Nations weren’t enemy enough, Katanga also had to cope with a rebellion of the Baluba tribe within her own borders. The Baluba, noted for their brutality and cannibalism, started massacring white families.

Instead of an army, Katanga had a gendarmerie of former ANC members. The Belgian army had pulled out, but not before seconding officers to the Katanganese. The leader of these men was Para-Commando Colonel Guy Weber. One of his men was Lieutenant Charles Masy.

To boost the numbers of the small gendarmerie, one of the Belgians, Carlos Huyghe, suggested that Katanga recruit personnel from white Africans and Europeans. This is where the Congo mercenaries started.

Without consulting the Belgians, Tshombe tried to recruit French Para-Commando officers, including legion paras. The French mercenaries demanded total control of the gendarmerie. The former CO of the French 3rd Colonial Para Battalion, Colonel Trinquier, was contracted as its commandant. However, when he tried to take up his position, the Belgians rerouted his plane to what is now Zambia.

Charles Masy remembers the period well: “Some of the worst trouble we had, including atrocities, was at the hands of the UN-troops, particularly the Sikh and Ethiopian contingents. They seemed to personalize it and were determined to crush Katanga.”

“We were based at Kongolo at the time, which is in the north of Katanga on the border with Kivu. The UN-troops attacked us on three occasions. They came at us very aggressively, not like these days when they have their hands tied.”

Besides the UN-forces, the mercenary army of Katanga had to cope with Congolese army deserters who had linked up with Baluba tribesmen and were engaged in ravaging the countryside. These tribesmen were unopposed by the UN-forces, whose main interest was to bring down the Katanganese government. In September 1961, the United Nations attacked the gendarmerie at Jadotville, in December at Elizabethville, and decisively beat them a year later, again at Elizabethville, thus toppling the Katanganese republic.

In what must be the sole surviving embassy of the old Katanga, Charles brings out memorabilia: copper-cross coins, the enameled badge of the gendarmerie, and two medals hanging from red, green and white ribbons. 4 ‘Moise Tshombe gave these to me himself,’’ said Charles. “This is the Katanganese Croix de Guerre. The crossed swords on it mean I won it twice. This is the Merits Katanganese. The palm leaf means I was also mentioned in dispatches.” Prominently displayed on a wall in Bar Simba is a large-scale map of the Katanganese republic. Behind the bar hangs the flag of the republic: a triangle of red meeting a triangle of white and united by a thin green line. On the white are three red crosses. “Copper crosses were once the currency of the region,” explained Charles.

“In 1962 the mercenaries left Katanga. The whites had lost about seven men out of a total of about 138 remaining mercenaries, which included French and Germans from the legion, Belgians, British and South-Africans. I really don’t know how many blacks died - a lot, the majority because of the UN-performance.”

“We headed for Rhodesia. I went to Nyasaland [Malawi], but the Brits threw me out because of my service in the Katanganese gendarmerie as an officer. When I arrived in Rhodesia, some friends showed me some ads in the newspapers calling for volunteers to join the Rhodesian SAS, which was in the process of being reformed. I was interviewed by the CO who, when he saw Katanga on my passport, told me to go to South Africa and get it changed.”

“I stayed in Rhodesia for about three weeks,” Charles continued. “Then one day when I came out of a tobacco shop I was arrested by two men who said they were immigration officials. I was held for two days. They asked me what I had done in Katanga, what I had done in Rhodesia, who I had met. They then asked me about Katanganese operations on 4th, 5th and 6th September 1961, after which they produced a detailed file.” It was obvious that the UN-authorities had compiled intelligence dossiers on all the mercenaries. “Finally,” said Charles, “they asked me: ‘How many did you kill?’ I was fed up with their games, so I said: ‘Not enough!!’ They put me on a plane for South Africa.”

"In South Africa I was given a job by a Belgian and worked there for about two years. But the Congo flared up again and Tshombe, now serving as president of the Congo, asked for mercenaries to help. Jack Schramme, a Belgian, formed 10 Commando, which was called Kansimba, meaning ‘young leopards.’”

Charles Masy again reached behind the bar and brought out a black embroidered patch with the words “Commando” at the top and “Kansimba” at the bottom. “This was Black Jack’s unit badge. It was worn on the left arm,” said Charles. “We have had some commemoration patches made up for the old 10 Commando hands who come in here.”

“A British ex-officer once approached me and suggested I go to the Congo because I knew the place. I was recruited in Johannesburg by Jan Gordon and left with the first volunteers.”

“Before Mike Hoare arrived on the scene, we were formed into commando companies. I was with 52 Commando [2nd Company, 5 Commando]. One of our most successful operations was against Simba at Boende. Twice we had to turn back after a 300-kilometer advance because we couldn’t cross the river. The town lay between two rivers that joined like a “Y.” We moved along the river about 12 kilometers and met a Belgian expatriate who organized boats which got us behind the town and we took it."

"Between Mibuta and Watsa we saved 1.489 Europeans. We were in action at Albertville, where we lost two mercs, a German and a South African - Koehtler and Nestler. They were killed on August 29th, 1964, in our first operation as 5 Commando. Later, the French formed a 6 Commando, which is less well-known. We re-equipped at Leopoldville and then moved to Coquilateville. After that we moved on to Stanleyville.”

“The worst for me was when we took Stanleyville. The massacre by the Simba had been terrible. I remember a young nun that the Simba had beaten and raped and then tied to a cart outside the convent so that passersby could rape and abuse her - she eventually died. Later, the mercenaries, acting as advisers, guided in both the Belgian Para-Commando Regiment [Operation Dragon Rouge] and Congolese army units. That was the climax of the Congo operation.”

Charles finally left the Congo as an officer in 1966 and returned to his native Brussels. He bought La Renaissance that same year with the money he had made during Congo service plus a year in service to the Portuguese. “Some other Congo mercs and I were approached by the Portuguese government. We went to Portugal for a year and trained for an operation which we were only told would be in Africa and entailed releasing a prisoner. Nothing came of it, but we got our wages,” said Charles.

Bar Simba, as it became known, rapidly became the haunt of those veterans of Europe’s forgotten wars. Legion veterans of every nationality regularly come through its door seeking a contact for work. Shortly after buying the bar, Charles was recruited through former Congo mercenaries to assist the Royalist government of Yemen in the civil war against the Egyptian/Soviet-backed republican government. Leaving his wife in charge, Charles set off for Yemen. “There were British SAS, French Para-Commando and legion and Belgian mercenaries,” said Charles. The mercenaries in the Yemeni war were some 48 in number - 18 of whom were Brits who had all seen service with 22 SAS. The remainder were French and Belgians under Roger Faulques - a legion hero who operated only with French government approval. The Egyptian and Soviet backers of the republicans used chemical weapons against the Royalists long before their use in South-east Asia or Afghanistan.

“Soon after I finished in the Yemen, the Biafran-Nigerian war started and so people came looking for me to go there. I declined and another Belgian took my place. Within three weeks he was dead,” Charles said.

“On another occasion three Belgians and an Italian were killed by a mortar strike. One of them had served with me in Katanga, another in the Yemen.” Recently, an Afghan came into the bar and left a small packet containing the personal effects of three Belgians whom he claimed had been killed in his country fighting the Soviets. He left names and asked Charles to find the next of kin - with no other clues to their identity.

La Renaissance is not an exclusive drinking club, but it is a special one. Said Charles, “Everyone comes here. Generals sit down and drink with privates. That is the way it is.”

Bron: Soldier of Fortune (63) | Jim Shortt | Augustus 1987